Reading Roundup: Arguing About Shakespeare

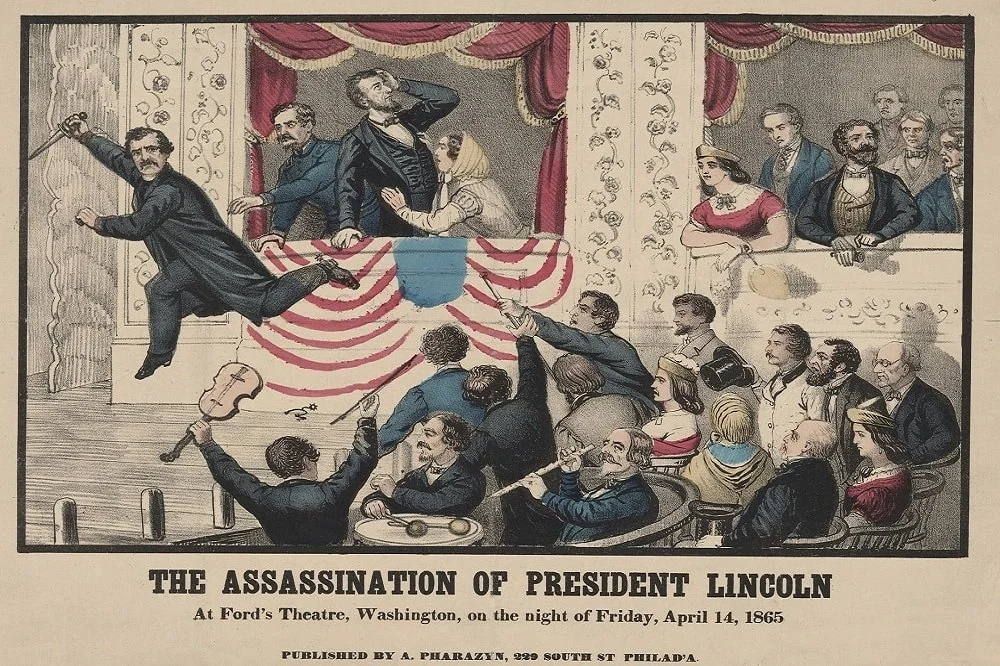

The assassination, in a theater, of a Shakespeare-loving president by a Shakespearean actor… one of the historical moments examined in James Shapiro’s book.

Remember when, in the dark days of 2020, I joined some friends in a virtual play-reading book club and we read the complete works of Shakespeare and then the complete plays of August Wilson?

I know the pandemic is ongoing, but I am very grateful that, two years later, I am in Ashland, Oregon for the first time since 2019, about to see some Shakespeare and some Wilson and some other plays with my Pandemic Play-Reading Book Club… finally hanging out with them in person and not virtually!

But I have some time to kill in the hotel before my first play of the trip (The Tempest… and it’s in the outdoor theater and it’s been raining hard all afternoon, lol) so I thought I would put up a Reading Roundup post of some Shakespeare-themed nonfiction. Ron Rosenbaum’s The Shakespeare Wars (which I read all the way back in 2019) focuses on contemporary debates in Shakespeare scholarship; James Shapiro’s Shakespeare in a Divided America takes the reader through several points in American history when Shakespeare became a locus of contention.

I made new friends during the pandemic thanks to Shakespeare; but it might be even more accurate to say that I made new friends thanks to arguing about Shakespeare. And these books prove that that has been a favorite pastime for hundreds of years.

The Shakespeare Wars: Clashing Scholars, Public Fiascoes, Palace Coups by Ron Rosenbaum

The Shakespeare Wars: Clashing Scholars, Public Fiascoes, Palace Coups by Ron Rosenbaum

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

Ron Rosenbaum really, really, really cares about Shakespeare. And he really, really wants you to care, too. He thinks it’s “scandalous” that there is a controversy over King Lear’s last words, depending on whether you go by the Quarto or the Folio; and he exults with schadenfreude when Professor Donald W. Foster is forced to recant his attribution to Shakespeare of a piece of doggerel called the “Funeral Elegy.” (Full disclosure: I took some classes from Foster at Vassar College around the time this book was published, and initially picked it up because of curiosity about what Rosenbaum had to say about my former professor.) For this book, Rosenbaum conducted extensive interviews with the greatest Shakespearean scholars, actors, and directors of the early 2000s, and always sounds absolutely delighted to be in their presence.

At times, though, Rosenbaum’s voice is too intrusive. In one chapter, he makes a thoughtful argument about why Shakespeare on film can be better than Shakespeare onstage, but it’s wrapped in a layer of “look at me, I’m such a contrarian.” In another chapter, he mildly embarrasses himself in front of his hero Peter Brook and then spends what feels like 20 pages in self-flagellation over his faux pas. And if a Shakespeare scholar implies that Rosenbaum (a mere ink-stained wretch of a journalist!) has said something clever or insightful about Shakespeare, he can’t resist patting himself on the back.

It’s also curious that, in a book whose stated aim is to introduce non-specialists to the major issues in Shakespeare studies in the early 21st century, Rosenbaum doesn’t look into feminist or postcolonial or queer theory. It’s fine if he’s personally more attracted to close textual analysis than to postmodern theory, but those theoretical approaches are a big part of Shakespeare studies these days and it’s odd that he didn’t speak to any scholars who specialize in those areas.

There are definitely times when I wish Rosenbaum’s editor had cut some of his digressions and repetitions, yet for the most part, his chatty style and incredible passion for Shakespeare keeps this a lively read.

Shakespeare in a Divided America: What His Plays Tell Us about Our Past and Future by James Shapiro

Shakespeare in a Divided America: What His Plays Tell Us about Our Past and Future by James Shapiro

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

James Shapiro is best known for his in-depth explorations of pivotal years in Shakespeare’s life like

A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare: 1599

, but in Shakespeare in a Divided America, he turns his attention to more recent history in his own country. The overall result is mixed: frequently impressive but sometimes muddled, just like this nation of ours.

The book starts off strong, discussing

Othello

and anxieties about interracial coupling before the Civil War. President John Quincy Adams was anti-slavery, yet also confessed himself “disgusted” by Desdemona’s love for Othello. It became a topic of national discussion when he expressed these views to Shakespearean actress Fanny Kemble and she publicly called him out on it. (Now I want to learn more about Kemble!)

The next chapter is less successful. Purportedly about Manifest Destiny, it’s really about anxieties over masculinity, the promotion of an ideal of vigorous American manhood, and the way female actors began to play Romeo after male actors started to find his personality too sentimental and romantic. But it kind of feels like Shapiro had a bunch of interesting anecdotes that don’t quite cohere.

Next, we learn about two moments when Shakespeare provoked real, consequential violence: the 1849 Astor Place Riots that broke out over conflicting interpretations of

Macbeth

(one populist, one elitist); and the 1865 assassination of a Shakespeare-loving president by a Shakespearean actor. I had never read such thorough accounts of these incidents and I appreciated the in-depth exploration.

The three chapters set in the 20th century deal with Shakespeare adaptations: a Caliban-themed pageant staged in 1916 to mark the tercentenary of Shakespeare’s death; the 1948 Broadway musical Kiss Me Kate; and the 1998 Best Picture-winner Shakespeare in Love. I enjoyed learning how

The Tempest

only became popular in America as immigration became a contentious political issue, and about how a seemingly fluffy musical really reflects all the gender anxieties of the post-war era.

But the Shakespeare in Love chapter is really muddled. Its subtitle is “Adultery and Same-Sex Love,” two different issues shoehorned together. Shapiro tries to point out the irony that Americans were flocking to see a prestige movie about an adulterous relationship while at the same time impeaching President Clinton for an adulterous relationship—and the additional irony that the film’s producer was the infamous Harvey Weinstein. But even Shapiro has to admit that no one in the press made these connections at the time (Weinstein’s crimes were not fully revealed till 2017), so it doesn’t really support his goal of describing moments in American history when Shakespeare reflected deep national tensions. Moreover, the problem with men like Clinton and Weinstein isn’t adultery per se; their predatory sexual behavior wouldn’t be any less creepy if they were unmarried. So if Shapiro is trying to convince us that Americans are hypocrites when it comes to adultery, Shakespeare in Love doesn’t seem like the best example to use. Maybe he should’ve stuck to the “same-sex love” theme for this chapter—because it was interesting to learn how original drafts of the screenplay much more frankly acknowledged that Will starts to feel attracted to Viola when she is still in disguise as a young man.

In the introduction and conclusion, Shapiro recounts his own recent experience with "Shakespeare in a divided America": he was a consultant for the notorious 2017 Central Park production of

Julius Caesar

, which featured a Caesar deliberately modeled after Trump. How strange that this, too, should now feel like history rather than current events. But this book came out in March 2020, the month when the pandemic hit and everything shifted. Although, even in the confusion and upheaval of those first pandemic months, we found ways to invoke Shakespeare. Perhaps Shapiro will have to put out an updated post-pandemic edition of this book with a new chapter exploring the “Shakespeare wrote

King Lear

during the plague” meme.